Digestive System Histology

GI Tract

Learning Objectives

- Describe the histological characteristics of the layers comprising each segment of the gastrointestinal tract and describe how they relate to their function

- Name and describe four transitional junctions in the GI tract

- Describe the topography of the gastric gland, its component cells, and architectural differences between glands in the three regions of the stomach

- Describe the structure of the small intestine, how its surface area is maximized, and the cells that comprise its epithelium

- Contrast the histological appearance of the large intestine from that of the small intestine

Lab Content

Introduction

The digestive system is responsible for the ingestion and digestion of dietary substances, the absorption of nutrients, and the elimination of waste products. The secretions of the associated glandular organs, such as the salivary glands, pancreas, liver, and gall bladder, aid the GI tract in accomplishing these functions. This laboratory will focus on the sequential segments of the gastrointestinal tract; the subsequent laboratory will focus on the glandular organs.

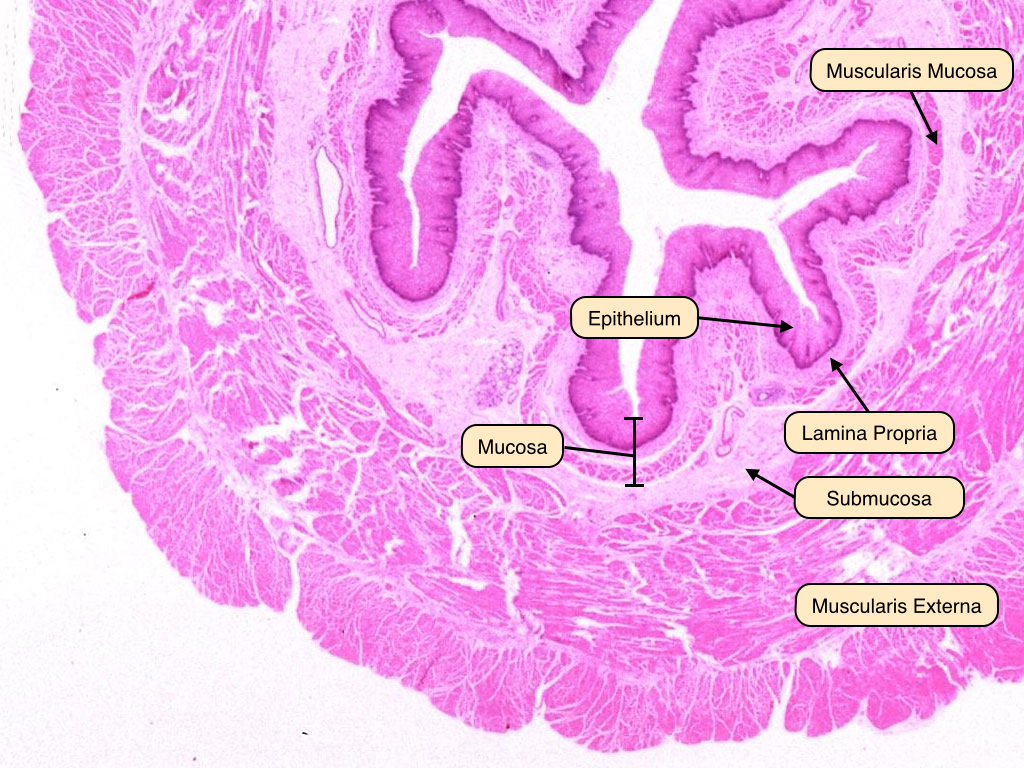

Basic Organization of the Gastrointestinal Tract

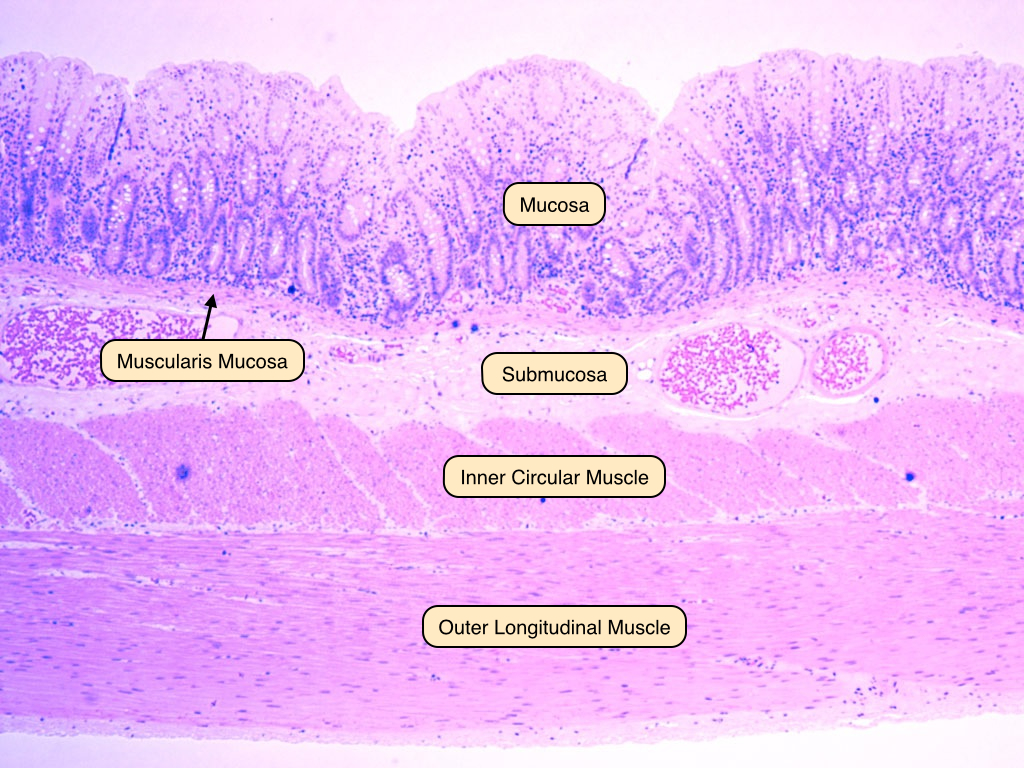

The GI tract is a muscular tube lined by a mucous membrane and features a basic histological organization that is similar across all of its segments of the tract. Several distinct, concentric layers line each segment of the tract:

- The mucosa surrounds the lumen of the GI tract and consists of an epithelial cell layer supported by a thin layer of connective tissue known as the lamina propria. The muscularis mucosa is a thin layer of smooth muscle that supports the mucosa and provides it with the ability to move and fold.

- The submucosa is a thick connective tissue layer that contains arteries, veins, lymphatics, and nerves.

- The muscularis externa surrounds the submucosa and is composed of two muscle layers, the inner circular layer and outer longitudinal layer. These two layers move perpendicularly to one another and form the basis of peristalsis.

- The adventitia consists of connective tissue containing blood vessels, nerves, and fat. In the portions of the tract within the peritoneal cavity, it is lined by the mesothelium. Recall from the Laboratory on Epithelia that the mesothelium is a specially named layer of simple squamous epithelial cells. In these tissues, the adventitia is referred to as serosa.

These four layers can be identified in most gastrointestinal segments, although different segments demonstrate important structural variations that can provide clues to their functions. The greatest structural variations occur in the mucosal layers. There are four distinct types of mucosal variations:

- Protective mucosa is characterized by a stratified squamous epithelium. It is found in the oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, and anal canal.

- Secretory mucosa contains cells that are responsible for the secretion of digestive enzymes. It is found exclusively in the stomach.

- Absorptive mucosa contains two key structures, crypts and villi, and is responsible primarily for absorbing digested nutrients. It is found along the entirety of the small intestine.

- Absorptive/protective mucosa specializes in water absorption and mucous secretion. It is found in the large intestine.

Esophagus

The esophagus is a muscular tube that transports food from the pharynx to the stomach. It is lined by a stratified squamous epithelium and has a prominent muscularis mucosa and thick muscularis externa. The muscularis externa of the esophagus is unique in that it transitions from striated to smooth muscle over the length of the tube. The esophagus ends in the gastro-esophageal junction.

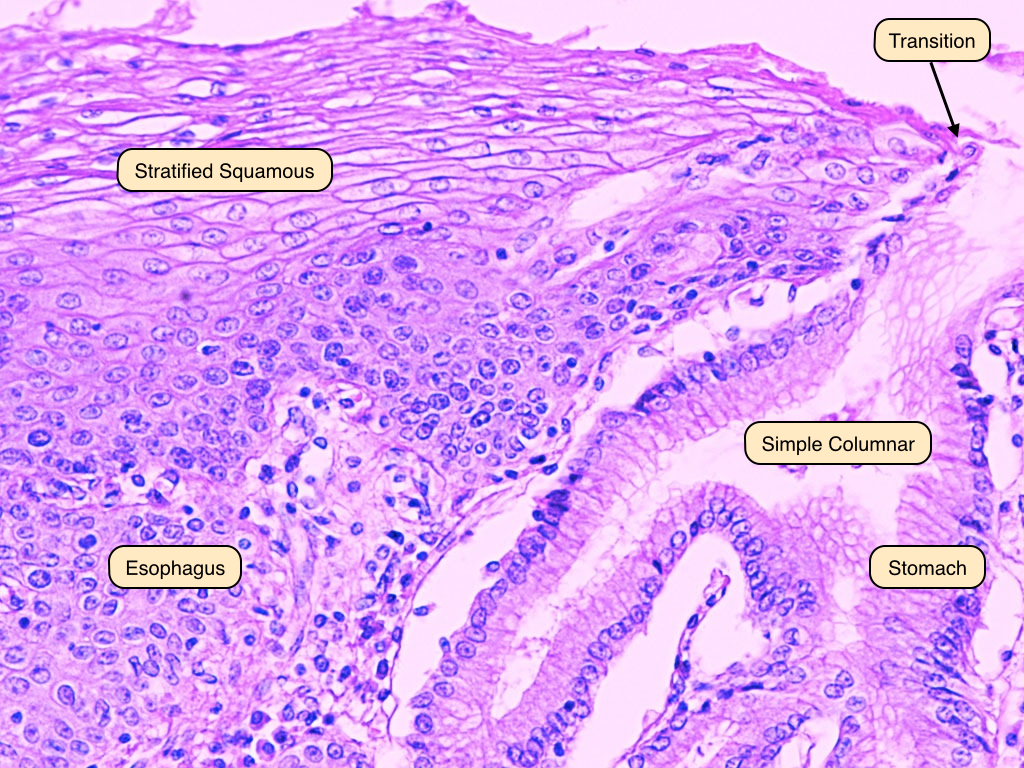

Gastro-esophageal Junction

The gastro-esophageal junction is notable because of the epithelial transition that takes place there. At this point, there is a shift from the stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus to the simple columnar epithelium of the stomach. Damage to the esophageal epithelium can cause metaplasia of these cells, known as Barrett's Esophagus.

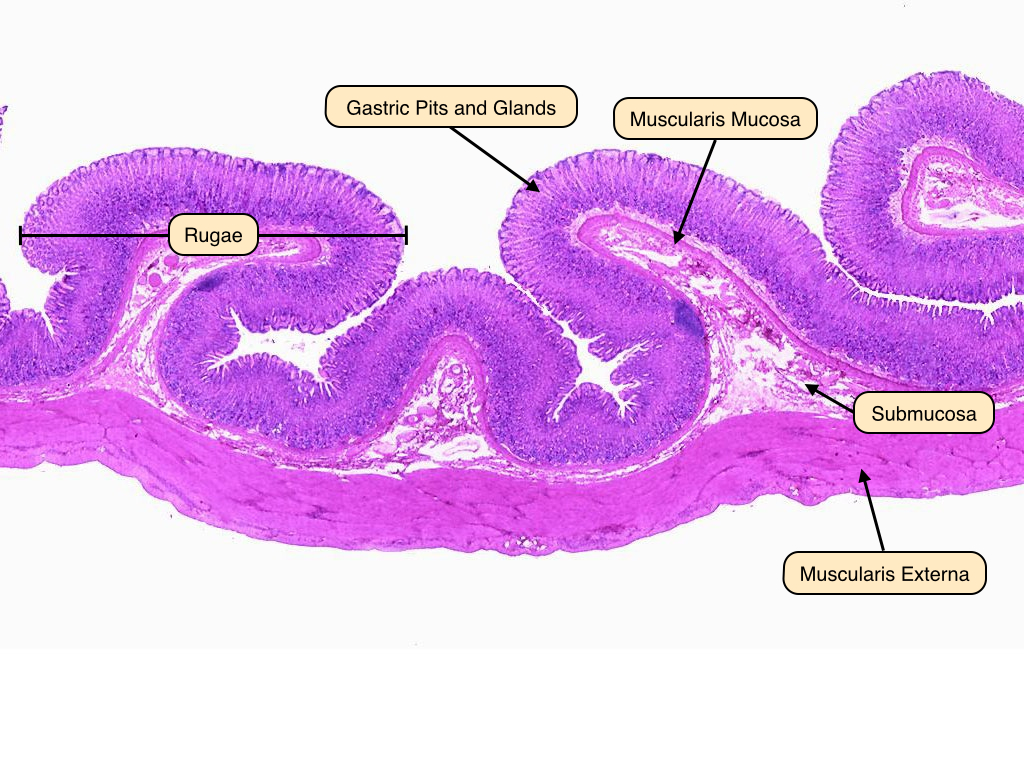

Stomach

The stomach is the site where food is mixed with gastric juice and reduced to a fluid mass called chyme. This slide shows the structure of the stomach lining under the light microscope. Begin by identifying the folds of the stomach wall, or rugae, which are visible in a gross specimen. The layers of the stomach wall follow the basic plan described above. The gastric glands are the basic structure of the stomach wall and can be thought of as tiny pits, or indentations, lined by epithelial cells. The loose connective tissue of the submucosa contains some blood vessels that can be discerned upon close observation. The muscularis externa of the stomach is notable because it contains an additional muscular layer. It is structured with inner oblique, middle circular, and outer longitudinal layers. This structure allows for the churning movements that mix the chyme and expose it to the acidic gastric juice produced by the stomach glands.

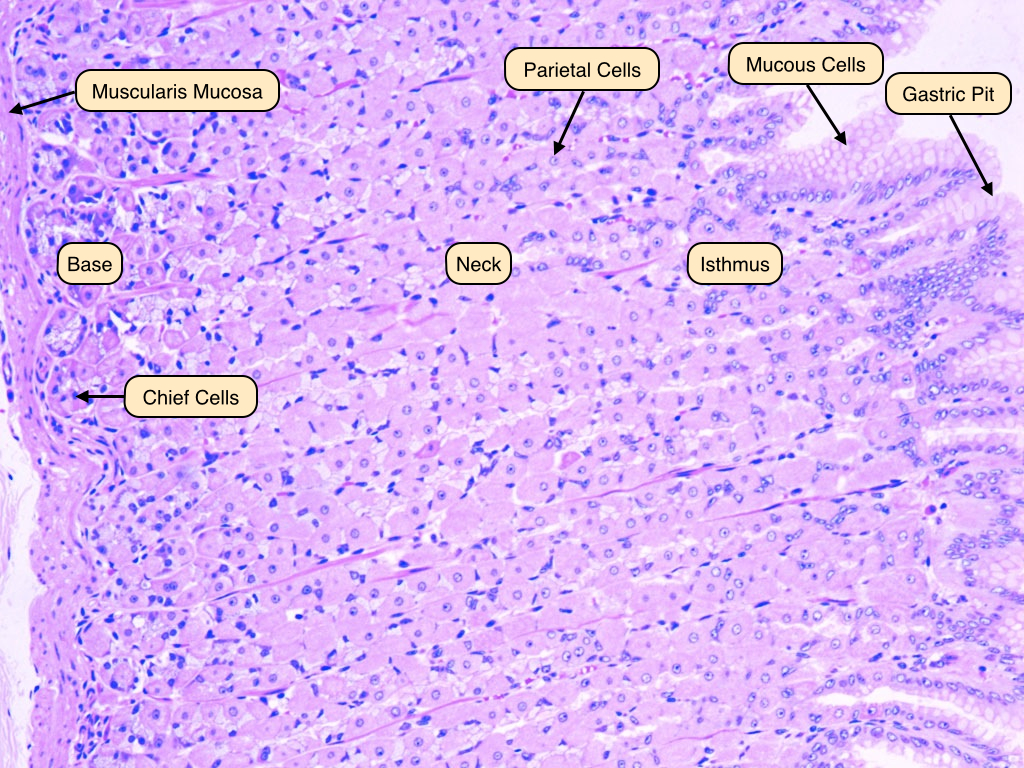

Gastric Glands

Gastric glands are structured as a gastric pit that opens into the lumen, followed by an isthmus, neck, and base. The mucosal layer appears here with its columnar epithelial cells, narrow lamina propria, and pink-staining muscularis mucosa There are several types of cells that are important in producing stomach secretions:

- Mucous-secreting cells produce mucous and bicarbonate ions, which protect the stomach epithelium from the damaging effects of stomach acid. They appear pale and contain obvious mucous droplets.

- Parietal cells secrete hydrochloric acid and intrinsic factor, which is important for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the terminal ileum. They have a characteristic pyramidal shape and are usually found in the isthmus of the gastric gland.

- Chief cells produce pepsinogen, which is stored in large apical secretory granules. After pepsinogen is secreted, it is converted by the acidic environment of the stomach to pepsin that is an active protease. Chief cells are found in the base of the gastric glands.

- Enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells produce histamine, which is important in the release of stomach acid. They are typically found in the base of the gastric glands.

- G-cells secrete the peptide hormone gastrin into the blood stream.

Small Intestine

The small intestine is responsible for the continued digestion and absorption of the GI tract contents. Reflecting its absorptive function, the surface of the small intestine is amplified significantly at three levels:

- At a gross level, the small intestine is a long tube into whose lumen projects the plicae circularis, circular folds of the mucosal epithelium, lamina propria, muscularis mucosa, and submucosa.

- Villi, finger-like projections involving only the epithelium and lamina propria, project into the lumen. They have a central lymphatic vessel known as a lacteal, which is crucial for the absorption of lipids from the intestine.

- Microvilli make up a brush border on the surface of the columnar cells of the mucosal epithelium.

The small intestine begins after the gastro-duodenal junction and is divided into three segments: duodenum, jejunum, and ileum.

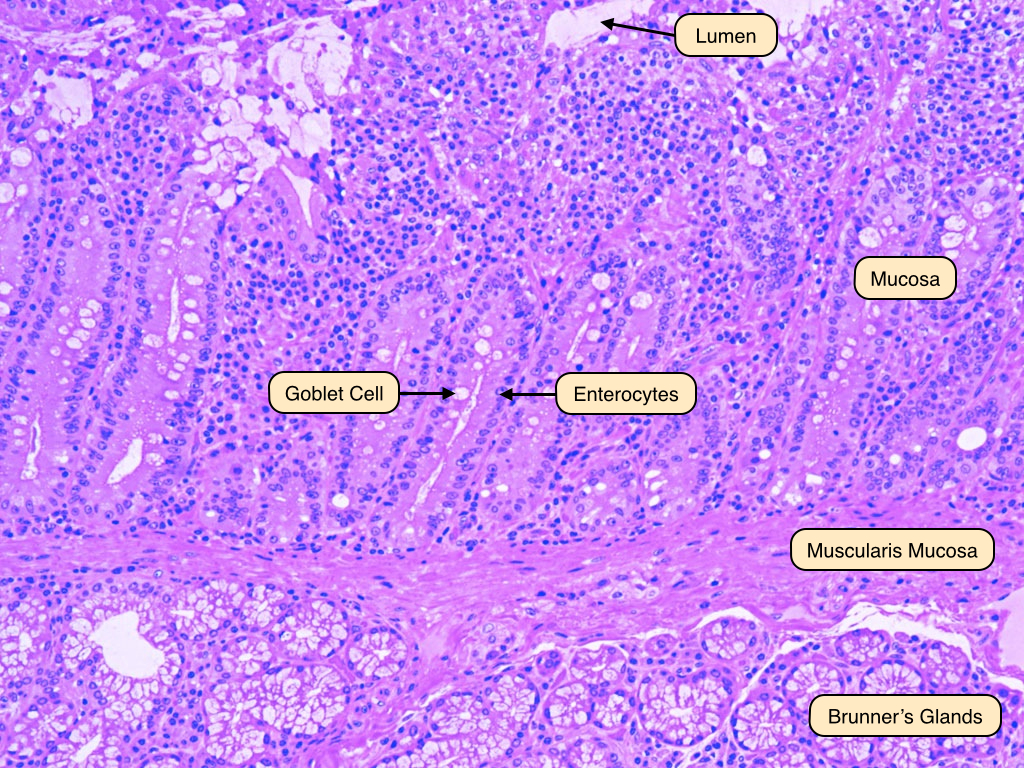

Duodenum

The duodenum contains the same wall layers seen in the previous portions of the GI tract: mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis externa. The epithelia and lamina propria of the mucosal layer are thrown into villi. Especially notable in this image are the Brunner's glands in the submucosa. These glands are unique to the duodenum. In the duodenum, pancreatic juice and bile are released into the lumen. Digestion is completed by enzymes in the pancreatic juice and on the surface of the epithelial cells where the products of digestion are absorbed.

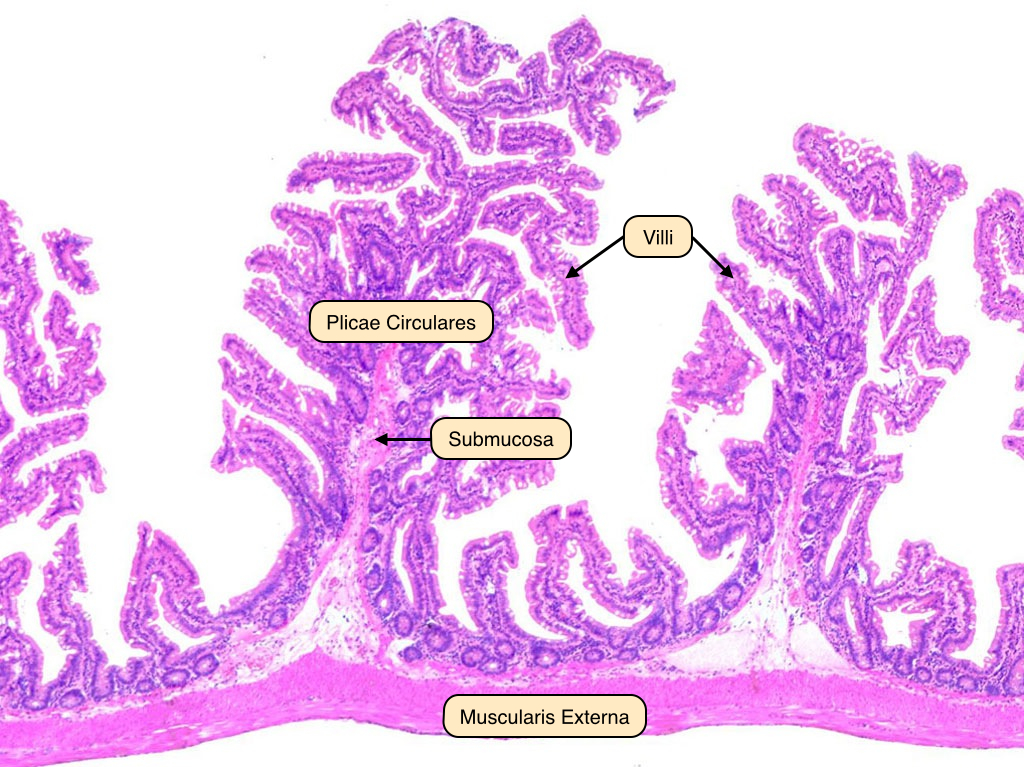

Jejunum

This cross section through the jejunum shows very prominent plicae circulares lined by numerous villi. Plicae circulares are more extensive in the jejunum compared to the duodenum and ileum. Plicae circulares are out foldings of both the mucosa and submucosa. Projecting from these folds are numerous villi that are outfoldings of the mucosa. Note that while the submucosa and mucosa extend into the plicae circulares, the muscularis externa does not.

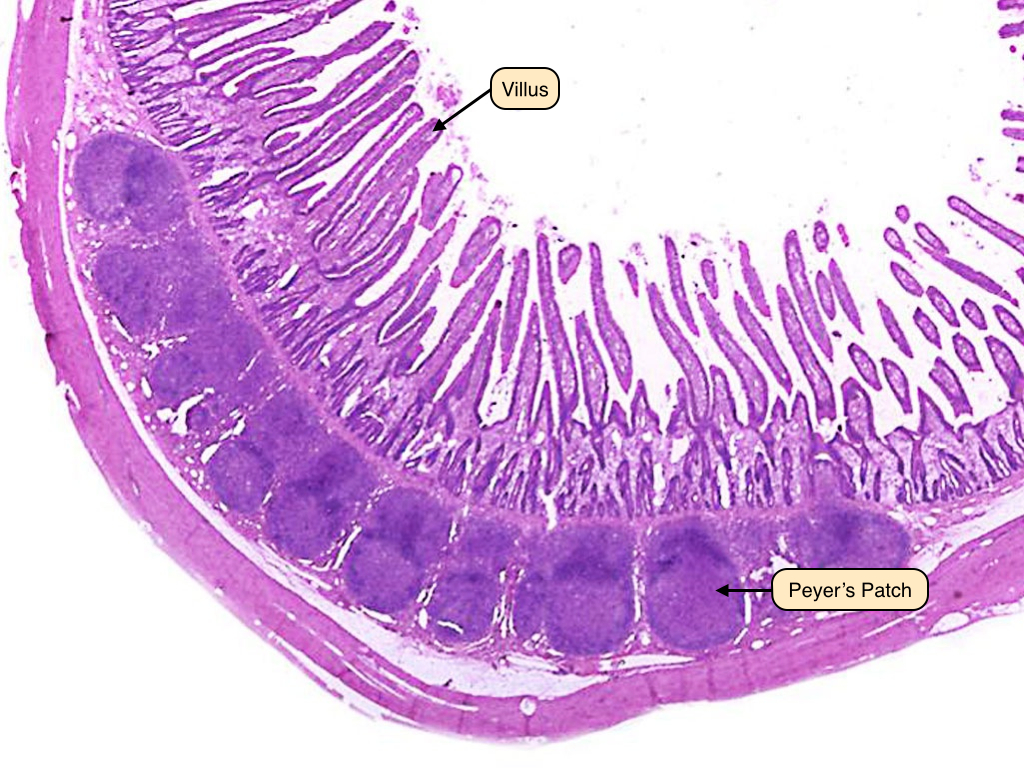

Ileum

This cross section through the ileum shows less dramatic plicae circularis compared to the jejunum. The villi remain quite prominent, but are shorter than those in the previous portions of the tract. The submucosal layer contains Peyer's patches, diffuse lymphoid tissue that play an important immunological role in sampling the contents of the tract. Peyer's patches are unique to the ileum. The muscularis externa is visible most externally.

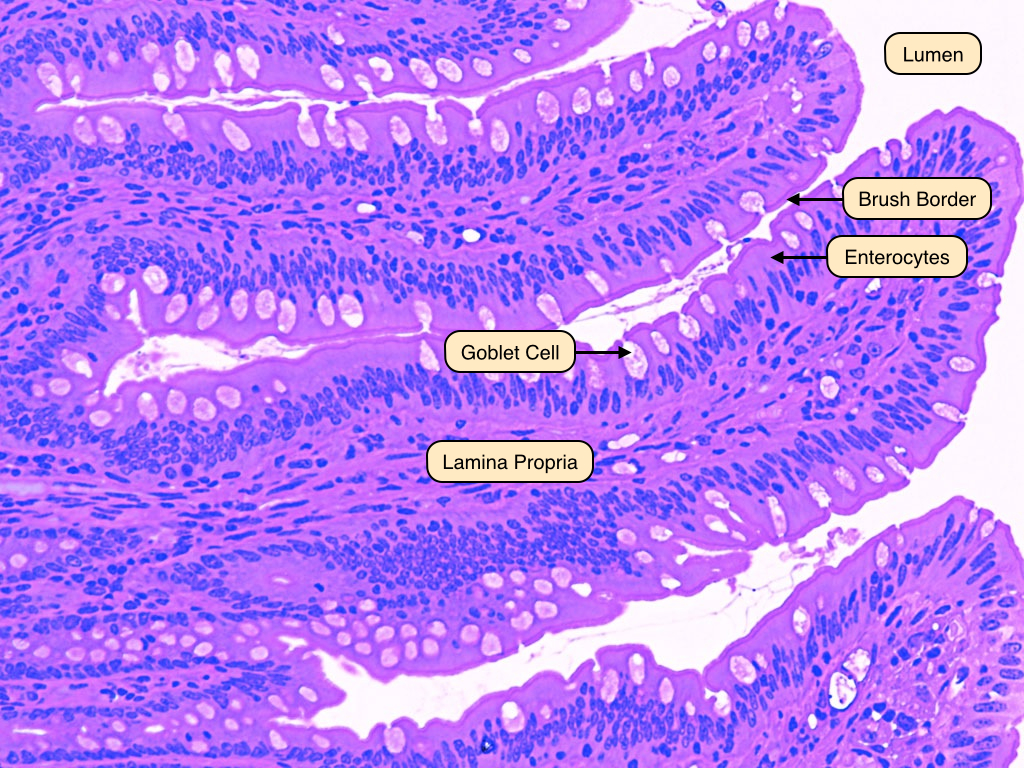

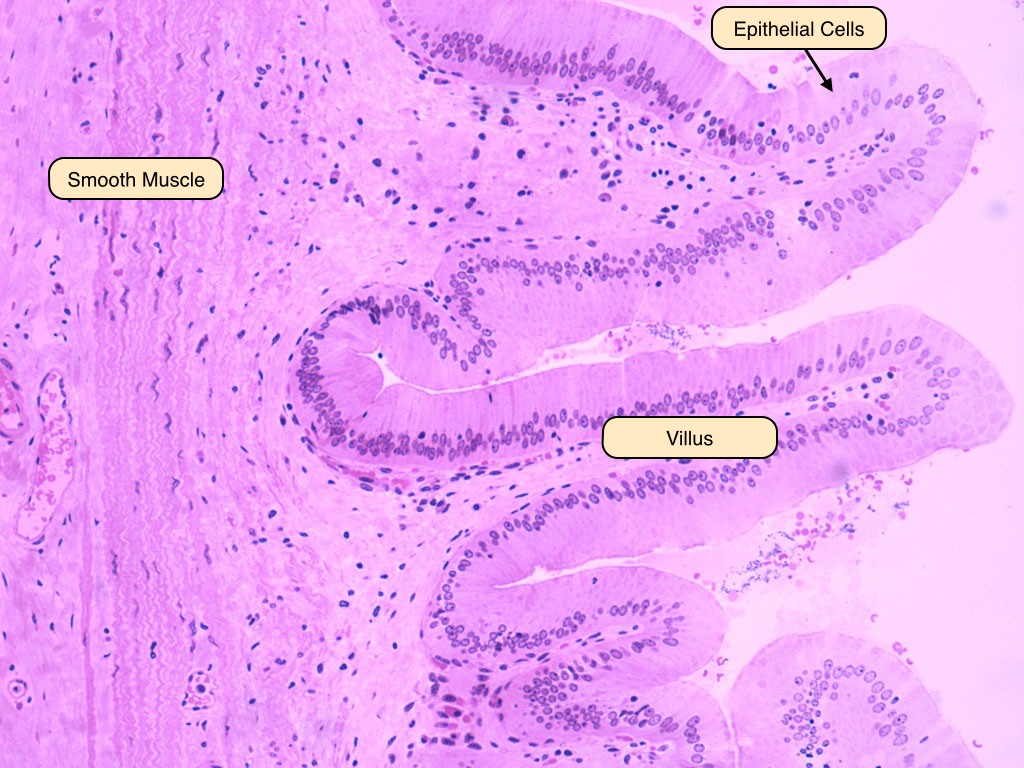

Villus

This light micrograph of an intestinal villus shows the important components of this structure. The villus is lined by epithelial enterocytes that contain a brush border. Enterocytes are the tall columnar epithelial cells that make up most of the intestinal lining and perform most of the intestinal digestive and absorptive functions. Goblet cells with their clear mucous droplets are interspersed between these enterocytes. The lamina propria supports the epithelial cells and makes up the core of the villus. Present in this layer are blood vessels, immune cells, and a lymphatic vessel, or lacteal, that is important for fat absorption. Villi also contain a strand of smooth muscle that cause them to move and mix the contents of the intestinal lumen.

Large Intestine

The large intestine absorbs water and concentrates waste material that is formed into feces. It lacks villi and contains a disproportionately large number of goblet cells. The lamina propria has many macrophages, plasma cells, eosinophils, and lymphoid nodules.

Pancreas

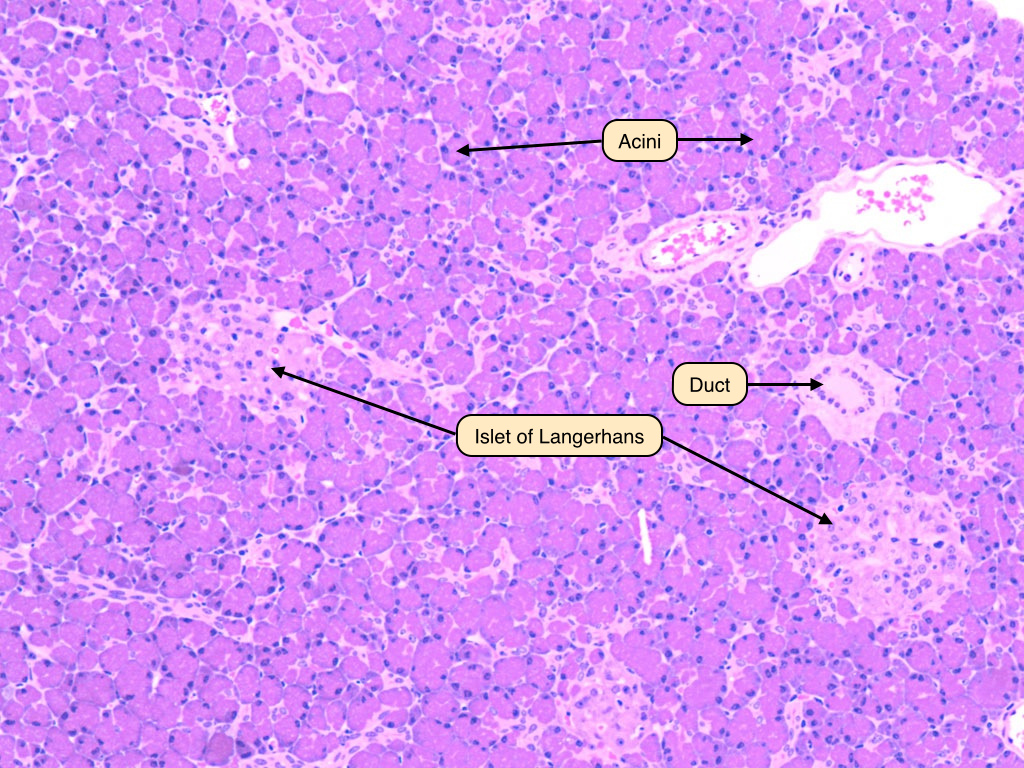

The pancreas consists of two functionally distinct parts: an exocrine part that produces digestive secretions that are discharged into the duodenum via a system of ducts, and an endocrine part consisting of the islets of Langerhans, which secrete insulin and glucagon to regulate carbohydrate metabolism. This image shows the two main functional domains of the pancreas. The endocrine pancreas that secretes insulin and glucogon is more lightly stained and its cells cluster to form the Islets of Langerhans. The rest of the image consists of the exocrine pancreas that produces several enzymes critical for digestion and adsorption of food. Note how the cells of the exocrine pancreas form small clusters or acini.

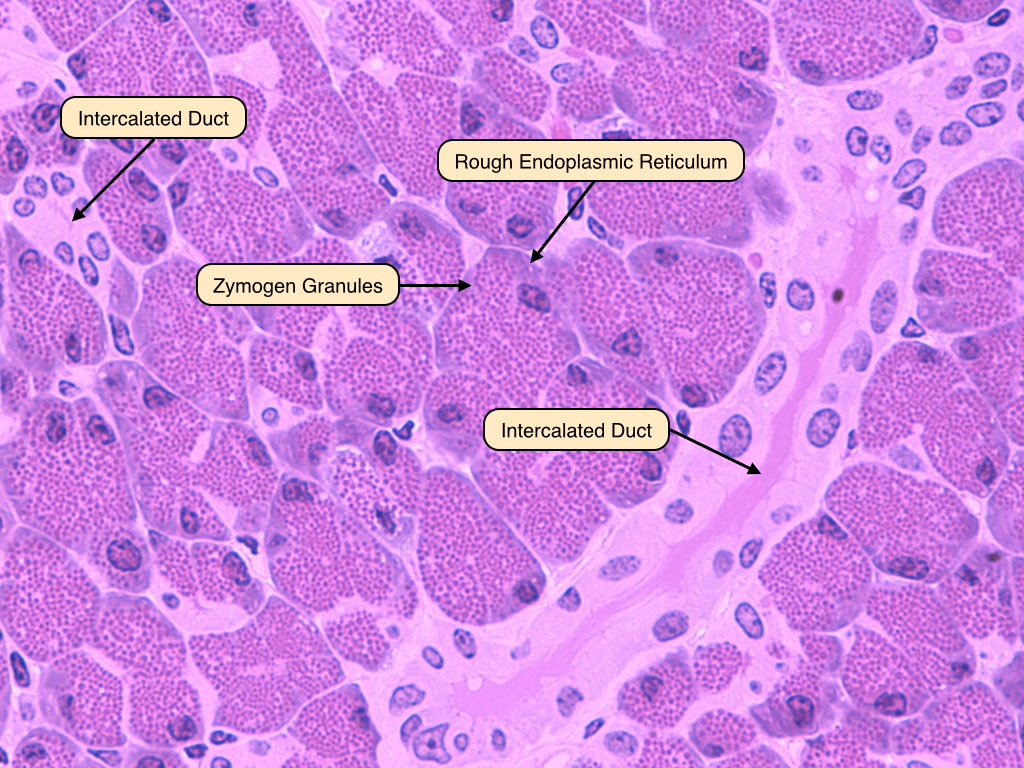

Pancreatic Acinar Cells

This section of the exocrine pancreas shows several of its characteristic features. The exocrine cells show a strongly basophilic cytoplasm that represents the area occupied by the rough endoplasmic reticulum. The apical side of the cells is filled with zymogen granules that contain a variety of digestive enzymes. Intercalate ducts are also visible. The cells which line the ducts secrete bicarbonate in response to secretin that is produced in the duodenum. Bicarobonate raises the pH of the contents in the duodenum. Also visible are centroacinar cells that form the terminal lining of the intercalated ducts.

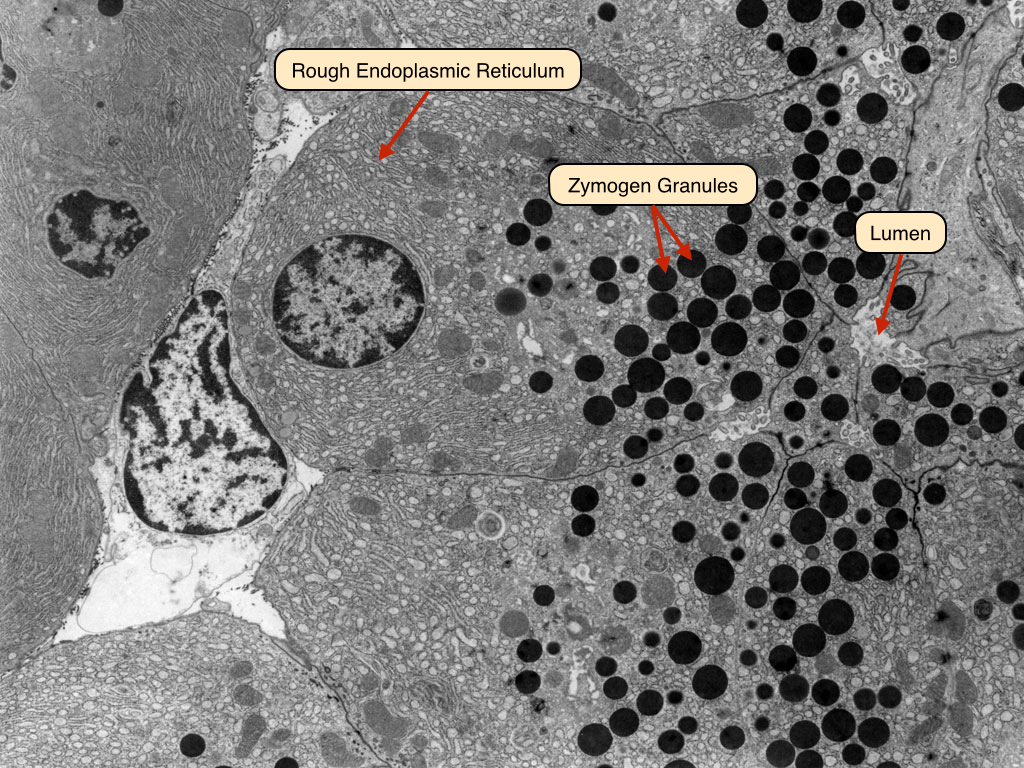

Pancreatic Acinar Cells EM

This electron micrograph shows in detail the acinar cells of the pancreas. These cells have basally located nuclei and numerous zymogen granules at their apical pole. They also have abundant endoplasmic reticulum in the basal portion of the cytoplasm. These cells will secrete their granule contents into the lumen of the duct, which will carry the enzymes out of the pancreas and to the duodenum.

Liver Organization

The liver is the largest organ of the body. Like the pancreas, it releases secretory products into the digestive tract. The liver has numerous functions:

- Secretes bile into the duodenum via the common bile duct.

- Serves as a highly efficient filter of portal blood from the intestine.

- Participates in large-scale synthesis and discharge of plasma proteins and lipoproteins.

- Detoxifies drugs and toxins.

- Plays a major biosynthetic and degradative role in regulating the macromolecular composition of the blood plasma.

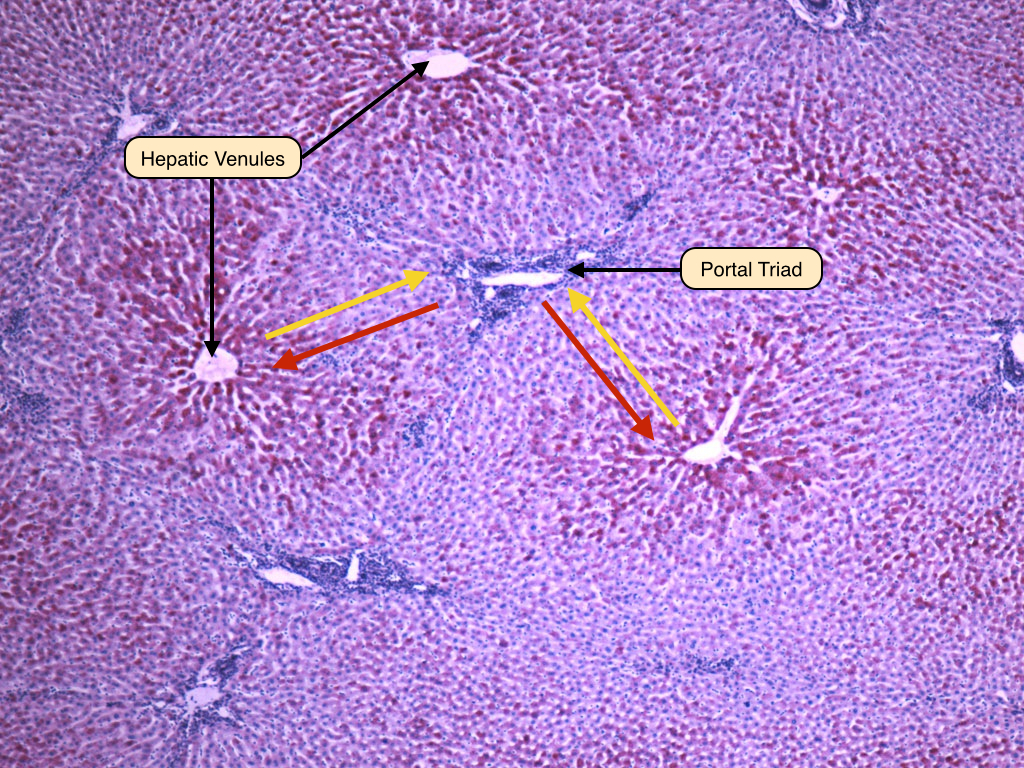

Portal triads convey blood into the liver and bile out of the liver. Hepatic venules surround portal triads and drain blood from the liver. In between the portal triads and hepatic venules lie hepatocytes that secrete bile and process nutrients, toxins and other material in the blood from the portal triad. The red arrows show the direction that blood flows from the portal triad to hepatic venule, whereas the yellow arrows show the flow of bile from hepatocytes to portal triad.

Portal Triad

Portal triads are composed of three major tubes. Branches of the hepatic artery carry oxygenated blood to the hepatocytes, while branches of the portal vein carry blood with nutrients from the small intestine. The bile duct carries bile products away from the hepatocytes, to the larger ducts and gall bladder.

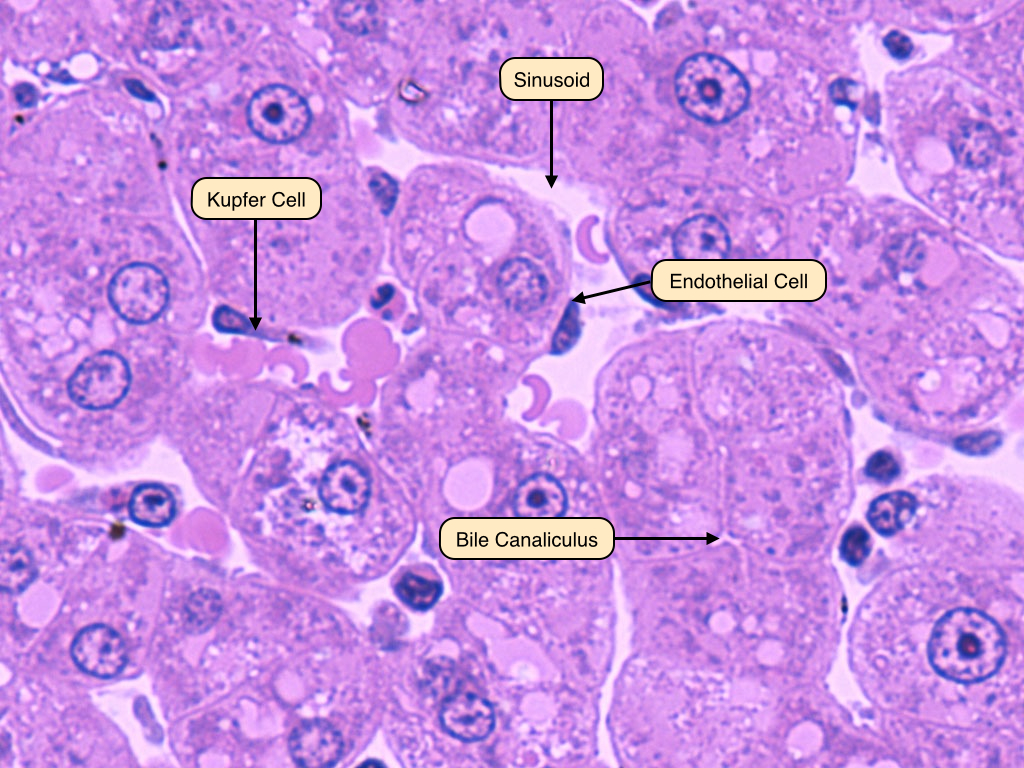

Hepatocytes and Sinusoids

This image shows the close proximity between the blood in the sinusoids and hepatocytes. Endothelial cells line the sinusoids. These endothelial cells form a discontinuous endothelium that has wide gaps between cells and lacks a basement membrane and is therefore very permeable. Hepatocytes secrete bile into canaliculi that are defined by junctions between hepatocytes. Bile flows through theses narrow tubes toward the bile duct. Also visible is a Kupffer cell. Kupffer cells are the resident macrophages of the liver and are typically found within the lumen of the sinusoids.

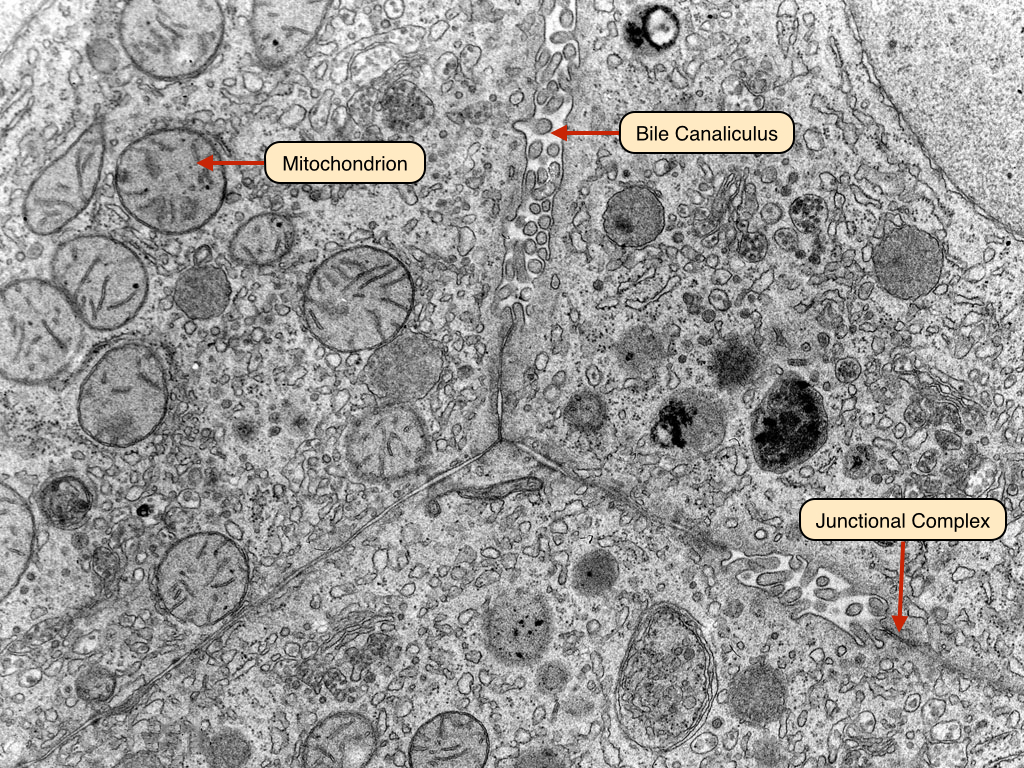

Hepatocytes EM

This electron microscope shows two hepatocytes separated by their cell membranes. A junctional complex is located near the apical portion of these cells. Above this junction is the bile canaliculus into which the cells secrete bile from their apical surface. Also available in these cells are numerous mitochondria.

Gall Bladder

The gall bladder stores and concentrates bile. It has several important characteristic features that can be used to distinguish it from other organs in the GI system. These include irregularly shaped villi that are lined by abnormally tall columnar epithelial cells. The smooth muscle in the wall of the gall bladder contracts under the influence of the hormone cholecystokinin to expel the bile into the duodenum.

No comments:

Post a Comment